When we meet artist Lani Mitchell she’s sitting in an Australian-run cafe, Two Hands, in SoHo, Manhattan. Mitchell is an abstract painter. She creates large-scale paintings, priced well outside the budget of most people her age. With no interest in being a “starving artist”, Mitchell knew that if she were to pursue a career, she would have to leave her comfort zone. She has now sold more than 90 paintings to collectors in Sydney, Newcastle, Melbourne and New York since her Artistry Galleries Exhibition in 2009, and a sold-out show in 2014 called SKIN.

Following the success of SKIN, Mitchell moved to New York and settled into a dreamy Williamsburg studio overlooking the East River. It was there in the thick of winter that she created her latest series, CHRYSALIS, and was quickly invited to exhibit at Parsons (the New School for Design).

Among the babble of Australian accents in the cafe, and the hum of Manhattan traffic, Mitchell discusses CHRYSALISand how it reveals her transition and growth, both artistically and personally.

Broadsheet: You’re an abstract painter in a time when a lot of artists are moving towards new media and technology. Why this medium? And why now?

Lani Mitchell: I was told painting wasn’t fashionable or trendy when I was at art school, which is probably why I felt so alien there and barely went – I worked in my garage at home, with my dad and brother. My dad let me destroy the front of our house, while my mother lamented that I wasn’t a mathematician. Dad’s palm trees were splattered in paint, so was his car, but he endorsed me and encouraged me to believe in my instincts. Feeling something was paramount. Painting made me feel, and I hope my paintings evoke that response in others.

BS: You left Melbourne almost immediately after your incredibly successful show, SKIN. What was your motivation for that?

LM: The challenge of the world’s most vibrant and overwhelming city, and arguably the epicentre of the art world, meant a potentially dramatic learning curve; not to mention a sink-or-swim experience. Without moving out of my comfort zone, I tend to stagnate, so the enormity of the challenge became compulsive.

BS: How does your experience of making art in Melbourne differ from New York?

LM: Melbourne is my hometown. It’s really comfortable and it meant a gentle beginning. I had the luxury of space in Melbourne; I paint large-scale, and on the floor, which worked well in my Balaclava studio, but it was really hard to find a studio here because New York is so space poor. SKINreflected Melbourne for me – my very social and playful lifestyle; friends would come in and out and bring me coffee and sit with me while I worked. Whereas CHRYSALIS is more pulled back and quiet, which reflects my experience of being totally alone in a New York winter.

BS: The harshness of New York winter is really resonant in CHRYSALIS, was that a conscious decision when creating the series?

LM: CHYSALIS is about metamorphosis, which has always appealed to me. It was not a conscious theme, but something I realised after creating the work, something that I felt I experienced through navigating a foreign climate and city.

First published for Broadsheet

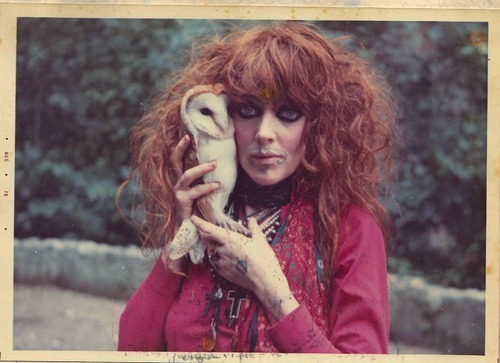

Photo by Alexander Sproule-Lagos